Now that we figured out main asset storage in Part I, we are ready to start figuring out how to get more out of the extracted files. I used the extractor and saved each individual file - there are 8132 files there. Running ls | cut -d'.' -f2 | sort -u gives us the following list: anm, bas, bdf, bin, bmp, box, cfg, def, des, hud, ion, itm, job, mnu, mp3, mpc, nws, ocf, pak, pal, pcx, pix, psd, pwf, scr, sen, spx, txt, vcs, wav, wng. These are all of the different file extensions. We can run GNU's file command on those to figure out what is a known file type and what isn't:

The command just takes the first file with such extension. I'm assuming all files with the same extension can be parsed with the same parser here (I later found that's not true in all cases in this game). I was quite surprised to see apple resource fork and a photoshop image in the dump. I quickly scanned the fork with hexdump and it appears to contain extra data about the photoshop image, so maybe someone copied something on accident into the archive? In either case it's fun exploring the pcx images and mp3/wav sounds. Lots of nostalgia for me; but that's not why we're here. The game is 3D... where are those 3D models?

I've spent some more time looking at Tachyon.exe - the parent function that opens the pff file reads the name of this file from another file kind that's called "RTXT" in the binary. After spending some time defining structures and renaming functions - I had a complete view of the RTXT file format. More over there was a very similar file format called "CBIN" - they are essentially ini files - have sections, keys and values. Except all strings are interned, and values can be a string, a float, or an int - and the binary version of the value is stored (as opposed to string).

Both follow approximately the same file structure, except CBIN is encrypted and uses the same decryption method discussed in part one. As you see the unknown fields are present - the code doesn't seem to touch them, but they are needed fro proper offset computation. Once you can parse those files you'll see that these two compose majority of the file in the game archive - bas, bdf, cfg, bas, des, job, mnu, nws, itm - are all either CBIN or RTXT files which again makes them essentially packed ini files, that can be loaded directly into memory without really much parsing - the format is definitely optimized for speed - and it shows - the game code actually just loads files into ram, quickly replaces any _offset fields to be actual pointer, and that's it.... Then the game uses the structs I showed above during all kinds of game logic to read game state or config - like how many credits you have.

After filtering out all the files that are CBIN or RTXT (side note - I should learn how to teach GNU file application to recognize new formats) we are left with *.pak, *.pwf, *.scr, and *.spx files. This is where some knowledge of the game itself can help, or you can explore those countless config files - the starting ship is called Orion. And there just so happens to be only orion.pak out of the extensions we can't read yet. More over orion.des is actually a config file which tells you info about orion as a game-object, and has a "PAK=orion.pak" config line. Ok so we need to figure out how to read pak files. Well it's time to open up space.exe in ghidra... WTF?

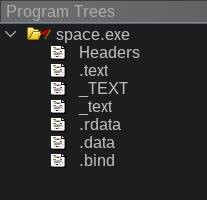

The entry point is giant 978 lines of decompiled C-code function that does oh so many function calls, XOR data decryptions, and random checks. That's not natural! Ghidra analysis also was not able to find too many other functions. So the binary is encrypted/obfuscated. My first reaction was to try and reverse engineer the obfuscator. I found some XOR keys and went looking at the data I could decrypt - it wasn't much help though as it seems the obfuscator would stage some code on the stack, execute it, then repeat the process several times. This is actually where my other problem lived - modern Linux, wine, Windows (and Macos for that matter) do not allow for executable stack. A while ago we figured out that that was just an open invitation to viruses, so operating systems quickly implemented "non-executable stack". But now wine can't run the game because as soon as the game tries to decrypt itself on the stack wine detects call to stack and crashes the game, thinking it's a virus. Proton, however seems to have that case handled correctly. (Side note, I've heard GoG version runs on wine natively. I don't know if they have a different version of the obfuscated code or what).

Well, I know proton runs the game correctly... let's see what the code looks like when the game is passed the obfuscator entry. At this point you need to know the difference between a program stored in an executable file versus running in memory.

All operating systems have a "loader" module, which takes an executable file stored on your drive, and load it into memory. The file on disk consists of several sections - .text, where the machine code of the program is stored, .rdata - where read-only data is stored. .data - where initial values of dynamic data are stored. There are plenty of other sections possible, but those are the ones we are interested the most. What happens is that the loader, loads sections into memory, maps the addresses correctly, and tells the CPU to start execution of whatever is the entry point. In our case the entry point is our large obfuscator. So there's a good chance the obfuscator does something and that something results in an actual game code being stored somewhere and executed. So once the game enters the main menu, at least some code needs to be deobfuscated. Later I learn that it deobfuscates just the whole game at a time and conveniently writes it all back into .text section in memory. That section just never gets stored back to the drive... We can fix that.

I'm not certain how to do this on Windows, but on Linux there are several ways to store all of the program's running memory to disk - it's called a core dump, and one of the ways to do it is to call $ gcore <pid> . You can find the pid by running ps aux | grep space.exe . This will cause approximately 2GB file to be created. Lots of tools can open core dumps. Since we're already using ghidra we can open the core dump in it! Watch out though - when ghidra asks to analyze the file - DON'T DO IT! It'll take more than an hour. At this point I also want to mention a challenge - I'm running a 64-bit linux, which uses wine to load a 32-bit windows game. This confuses ghidra because it assumes a single file is meant for a single target platform. Luckly this doesn't affect us - I looked at the core dump's .text section and manually compared its random offset with data in space.exe - and it was different! So I extracted this data into a separate file, then opened original space.exe and replaced its .text with the newly extracted one... Voila!

We know it worked because we were able to re-analize the file and find a LOT more functions. What's even better is that we were able to find a lot of imported functions. This is where knowing basics of windows development can help - to create a window someone needs to call the CreateWindow* function:

This function has only one reference:

I've spent some time recovering UI context - you'll see a lot of DAT_ values instead. Let's go back to looking for info about our pak files! To make life a bit easier I also loaded the .rdata and .data sections from our core dump - the more the merrier in this context:

If you see some of the UPPER_CASE strings and search for those strings in the extracted game files you'll find that *.des files have EXTERIOR_PAK key that points to ship's pak.While good approach in general - in our case there's a lot of references to this string:

We can also look for more strings, or do the trick with fopen. There's a lot of "try different strategies" here. What I did was I went to look for strings that I was already familiar with from the game launcher - Tachyon.exe. Since the game reads the same resource file - there's a good chance that the exact same functions are in it. I ended up finding this function - file_OpenEx (I know its name because it logs its name on error). From there I went back up the XREFs of file_OpenEx and marked every argument that is a filename passed to file_OpenEx. It so happens that FUN_004b14b0 calls file_OpenEx, and at some point gets called with "moveroid.pak" filename. So it's a good chance that's our PAK parser! We are going to go over it in Part III.

No comments:

Post a Comment